Can Airbnb Be Regulated?

Back in 2017, the City of Toronto passed new bylaws governing the use of short-term housing rentals within the City limits. Colloquially, this became known as the Airbnb by-law. However, the by-law was never implemented as an appeal to the Local Planning and Appeal Tribunal (LPAT) was filed and halted all progress.

That appeal was finally resolved in November of 2019, with the LPAT approving the City’s original proposal. As the City puts the finishing touches on its approach, it is worth exploring the pros and cons of the City’s policy and what it may mean for municipal policy makers in Ontario’s other 443 municipalities.

The Case to Regulate – Toronto:

When Airbnb was created in 2008, few people could predict the fundamental impact it would have on the tourism industry or housing policy more generally. In Toronto alone, more than 8,000 properties are listed on Airbnb at any given time, with approximately 65% of them being entire homes for rent.

Though disputed by Airbnb, the rental advocacy group Fairbnb has argued that as many as 6,500 properties are withheld from the housing market in Toronto to instead be permanent short-term rental residences. Meanwhile, the City has more than 100,000 people on its affordable housing waitlist and an average home sale price of just over $852,000.

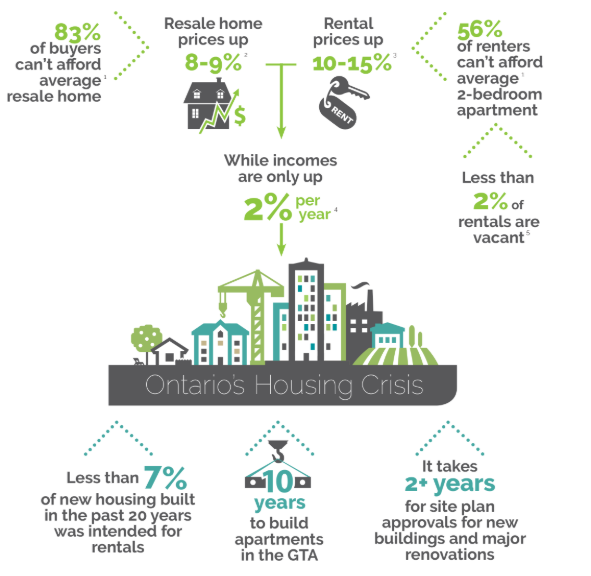

According to the province (see graphic below), it takes up to 10 years to build an apartment in the Greater Toronto Area despite the City having a vacancy rate that routinely hovers just over 1%. The slow pace for new builds coupled with high resale prices has led to a housing affordability crisis. If regulating short-term rentals returns anywhere near 6,500 homes to the market, it could have a large impact on housing prices.

Further, short-term rentals have been the subject of a variety of resident complaints about noise, violence and vandalism. Between 2014 and 2019, the City estimated it received over 500 resident complaints with the Toronto Police Service responding to 127 separate incidents at short-term rental properties.

Further, short-term rentals have been the subject of a variety of resident complaints about noise, violence and vandalism. Between 2014 and 2019, the City estimated it received over 500 resident complaints with the Toronto Police Service responding to 127 separate incidents at short-term rental properties.

A combination of these factors has led Toronto to follow the lead of other major cities, like New York City, and introduce a set of regulatory requirements for short-term rental property owners and hosting sites, such as Airbnb or Kijiji.

The Regulations – A Breakdown:

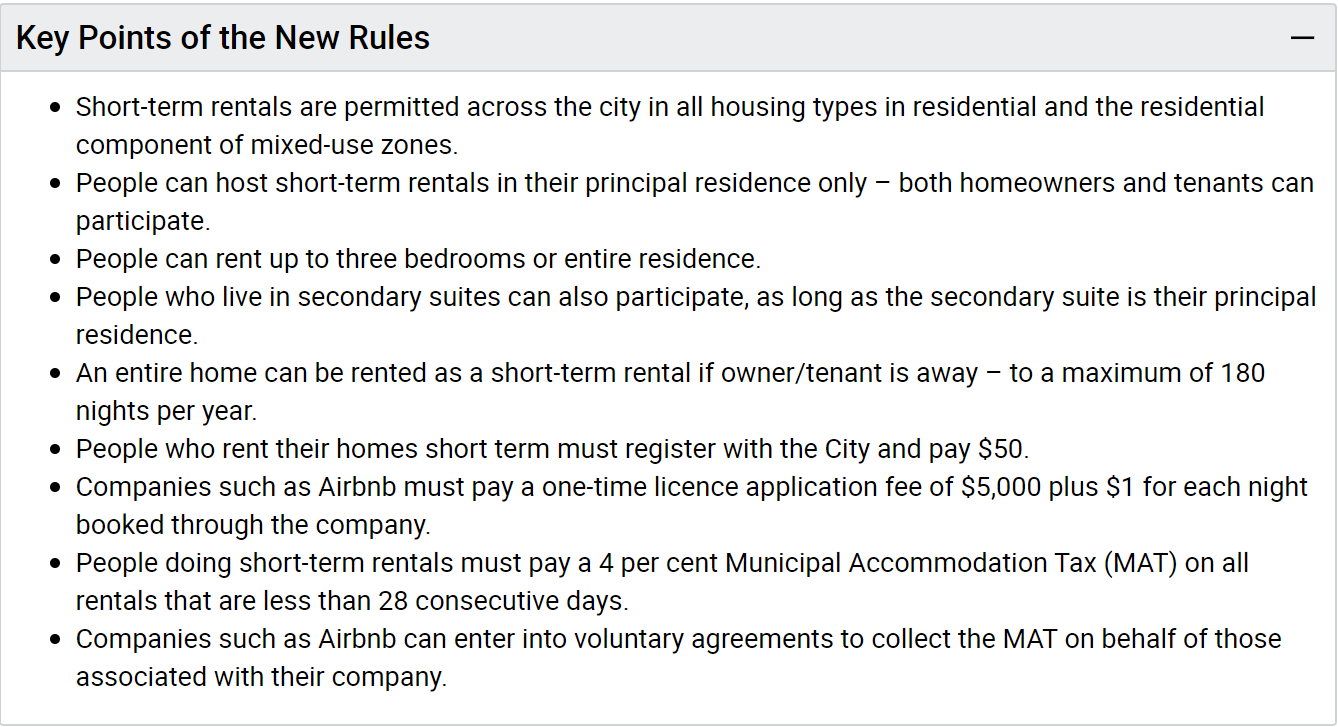

The now approved City regulations set out a variety of new rules and stipulations, listed below:

The Good:

Chief among the new rules is the limitation that a property can only be rented if it is the person’s principal residence. This provision would target landlords that own and list multiple properties, commonly called ghost hotels, while not punishing the average family or homeowner who is looking to make a little extra revenue. It will however be difficult to enforce, given the principal residence declaration will almost surely be by attestation only. To rectify this, the City could explore partnership opportunities with the Canada Revenue Agency to do a quick verification of principal residence attestations.

The second area where the City put forward a positive solution is the suggestion that owners or tenants in secondary suites (largely basement apartments) can also participate. The City has an estimated 70,000-100,000 illegal secondary suites that are filled by short-term rentals and longer term leases. Secondary suites are largely seen as a cost-effective way to combat a lack of affordable housing but come with resident concerns over increased population density.

By including secondary suites in the short-term rental policy, the City is indirectly encouraging the creation of more of these units. This will be especially true if the new regulations reduce the amount of condo or apartment units competing with homeowner’s secondary suites for short-term rental revenue. If secondary suites were not included in these rules, homeowners would have even less incentive to renovate their basement to accommodate tenants.

The Bad:

The City appears to have missed the mark in two different areas. First, they are charging both a 4% tax on all rentals, called the Municipal Accommodation Tax, and a $1 fee to the hosting site per night booked. The City decided to both tax renters and levy a fee on hosting sites. It is almost guaranteed that these hosting sites will simply pass the cost along to their customers. Given that the customer will likely pay both the tax and the fee, the City could have saved the administrative headache of charging through two different mechanisms and just charged one larger premium.

Second, the City has allocated just five full-time staff to enforce the regulations. Given there are more than 8,000 properties listed for short-term rental at any given time, it will be a herculean task for these staff to actively monitor their compliance. Instead, enforcement will likely only occur after a complaint is made. Without proactive enforcement, the City will have a very difficult time ensuring properties are principal residences only or have been booked for less than the maximum 180 night per year limit.

The Unintended Consequences:

The regulation includes existing bed and breakfast establishments as short-term rental properties. That means that anyone who was operating this style of business within the city limits is now limited to 180 days of renting a year and are limited to renting only 3 bedrooms at a time. Though this is likely a very small industry within the City of Toronto, the regulations will likely kill any traditional bed and breakfasts that exist by making their business model unworkable.

Another unintended consequence is likely to be the increase in usage of non-verified hosting sites. Even though Airbnb is unregulated, it does do some self-policing through a public consumer rating system of landlords and tenants. Airbnb even removes properties from their site if serious complaints are levied. By making short-term rentals harder to list or more expensive to rent, enterprising people may use non short-term rental sites like Facebook and Craigslist to circumvent the rules.

An even more elaborate consequence of regulation in New York City saw owners of multiple properties skirt the rules. These landlords created multiple different host accounts on the sites, found fake tenants to declare the property their principle residence, and even used fake identities or new immigrants to run their multiple bedroom operations. These situations have led to New York City launching complex investigations and filing multi-million-dollar lawsuits against problem landlords. More positively, it has also led to an eventual agreement between the city and Airbnb to share data to attempt to weed out the bad actors, something Toronto could be wise to pursue.

There is a very real possibility that the owners of multiple properties that the regulations are attempting to target will have the easiest time avoiding the rules. Meanwhile, law abiding hosts who were looking to make a few extra dollars will now have more rules and fees placed on them even though they were not the recipients of complaints.

Lessons for Other Municipalities:

Even though Toronto has picked a path that may work for it, other municipalities will have to decide if they want to regulate the industry at all and, if so, how. Larger cities like Ottawa and Mississauga may be able to follow Toronto’s lead and create similar rules, but rural and Northern municipalities that have high amounts of tourist based short-term rentals may want to shy away from such aggressive regulation.

In heavy tourist towns without more traditional accommodation options like hotels, Airbnb and short-term rentals are an economic boost. For example, the impact to Prince Edward County’s wine industry if access to short-term rentals was reduced could be devastating. Tourist driven municipalities may want to crack down on short-term rental properties for noise violations and petty-theft, as is being considered in Oro-Medonte, but will likely want to shy away from any policies that severely limit listings.

In tourist towns that do have traditional accommodation options, like the town of the Blue Mountains or Wasaga Beach, regulating short-term rentals is a very realistic option. In fact, in the skiing town of the Blue Mountains registration of a short-term rental property cost $2,500 with a renewal fee of $1,000 every two years. Those municipalities that derive significant revenue from local hotels and surrounding businesses that have made large investments in the community have even more incentive to regulate short-term rentals. When short-term rentals undercut traditional accommodations, it puts future investment and continued tax revenue at risk.

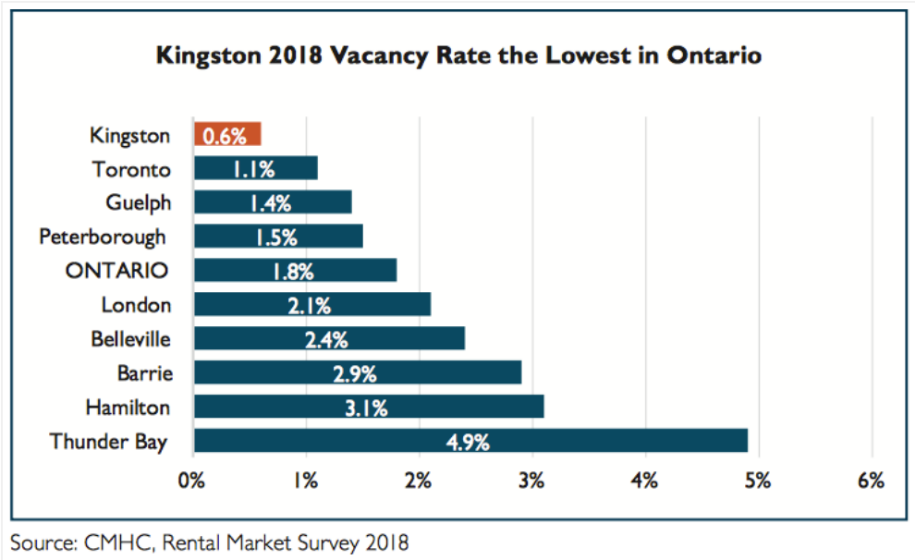

In mid-size municipalities, it may depend on the housing situation that they are faced with. For example, the City of Kingston has recently had a lower vacancy rate than Toronto, hitting a record low of 0.6% vacancy in the city limits. For those cities, they may have a desire to pursue strict regulations that would encourage housing back onto the open market.

Finally, the province will eventually have to decide if it wants to get involved in a provincial framework for short-term rentals. Individual members of provincial parliament have previously introduced legislation and the provincial government has previously held consultations and created a guide to municipal regulation on the topic. However, discussions of provincial regulation have been quiet as of late and the current administration has generally shown a desire to empower municipalities to make decisions that work best for them.

Conclusion:

Now that the City of Toronto has final approval to regulate short-term rental properties it will need to move to implementation. In doing so, it will be important to evaluate if the regulation achieves the goals it was designed to achieve – more housing supply, less ghost properties, and fewer bad actors. Not only will housing advocates want to see the results, but several Ontario’s municipalities will be watching closely as well.