Does Community Buy-In Still Matter in Today’s “Pro-Development Environment”?

Under the pall of a housing affordability crisis and significant shortfalls in new home supply, the 2022 Ontario election campaign was dominated by the parties working to outmuscle each other on housing, each promising record levels of new construction. Not coincidentally, the eventual winners distilled their pitch down to this: “Only Doug Ford and the Ontario PCs will build 1.5 million homes over 10 years.”

It’s an interesting moment in the politics of land development. The Premier has promised to build 1.5 million new homes over ten years. Provincial planning policy is aligned and picking up steam with Bill 23. Interest groups across the spectrum—from Ontario’s Realtors to environmental groups—have backed the push for many more homes (and ASAP).

Does this mean that traditional community engagement for new development has been upended? Perhaps developers no longer need to supplicate themselves before local leaders and residents, begging for a little more height or density. Maybe Ontario is now a developer’s field of dreams but without the “if”—yes, you can build it, because we know they will come.

So while most Ontarians agree we need more housing, and lots of it, a critical question lingers. Where?

The Death of NIMBYism Has Been Greatly Exaggerated

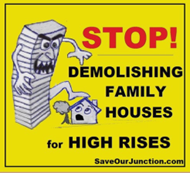

Supporting development so long as it’s located somewhere else remains a commonly held sentiment. And despite the policy-level consensus, NIMBYism hasn’t gone anywhere. In Toronto, this election season heralded a return of anti-development lawn signs (“Stop Demolishing Family Houses for High Rises”).

This type of messaging must still work, even as Toronto City Council recently passed a housing plan that took bold steps toward ending single-family zoning in the city. Opponents of the housing supply surge largely continue their fight: the day of its announcement, one Toronto councillor called the approved housing plan “a death blow” to neighbourhoods like those in his ward.

And while recent changes have been successful at legalizing duplexes or adding gentle density, individual large-scale projects across the province are still being rejected for the same reasons they always were. Well-organized community members continue to say a development is too tall, has too many units, is out of character for the area, or won’t have enough parking. It’s happened in the past few months for a townhome community in Guelph, 1,600 new apartment units in Kingston, and a high-rise in London. In some cases, developers will appeal to the Ontario Land Tribunal, or perhaps the project will be resurrected with a Minister’s Zoning Order. Even if such a reversal arrives, it may take years, and many proposed developments cannot survive that long. More to the point, a pattern of reject-and-appeal is hardly synonymous with a new climate for development in Ontario.

A New Opportunity in Community Engagement for Land Development

Despite the provincial mandates and rhetorical commitments to housing, the reality is that all new developments will still have neighbours. Those neighbours will mobilize and vote, and city councillors will feel pressure from their most active and established constituents. The era of “all politics is local” is not over.

In fact, the opportunity to work collaboratively with proactive community members has never been greater. The conversation around housing supply and affordability have spurred action. Self-organizing YIMBY (Yes In My Backyard) groups are emerging in communities across the province. If engaged properly, they can activate their networks in favour of a development project, using social media to organize, email councillors, and arrange deputations to counterbalance criticism at public meetings.

Engagement Still Matters

The climate around development may change in the future, so it’s worth considering that this moment may be fleeting. Legislative amendments, a leadership shakeup, or just sagging government approval ratings in key ridings may be enough for the Province to revert to policies that can frustrate new developments. Yet we know reputation management and meaningful community engagement will always outlast a particular policy environment.

For all these reasons, a hands-off approach to community engagement remains a risky endeavour. Even if a developer can secure approvals solely by relying on planning policy and pro-developer sentiment (whether at OLT or via the traditional planning and zoning process), few large projects do so without friction.

Stoking resentment among nearby residents and businesses is a difficult way to begin the long-term relationship between developer and community. The perception of a developer being unresponsive to the opinions of neighbours may also create challenges for marketing, sales, or leasing—and that’s before considering the impact on the company’s overall reputation as it pursues the next proposal that’s not permitted as-of-right.

While the Planning Act may be changing, the law of gravity isn’t; early and consistent consultation and collaboration can still avoid these pitfalls and set up developers for future success. In short, local stakeholders still matter. Reputation still matters. Community engagement still matters. It may just be the difference between the same old land use politics and seizing this ‘build it’ moment.

RELATED:

- Read StrategyCorp’s analysis of Bill 23 – Breaking down Ontario’s new housing changes

- Listen to Sabine Matheson and Aidan Grove-White discuss the bill’s impact on the Intended Consequences podcast