Addressing Mental Health Care Wait-Times for Students

By Mitch Davidson, Sara Bourdeau and Laura Oprea

The cold and dark days of January can be a difficult time for many people, especially when combined with post-holiday season fatigue. This time of year can be even more difficult for post-secondary students leaving their families and returning back to campus. On top of this, for many students, this is a time of firsts: first time living away from home, first time juggling a difficult course load with a part-time job or an internship, and their first time experiencing the strain of finances or personal relationships. All told, the winter months can be a difficult emotional and mental situation for post-secondary students.

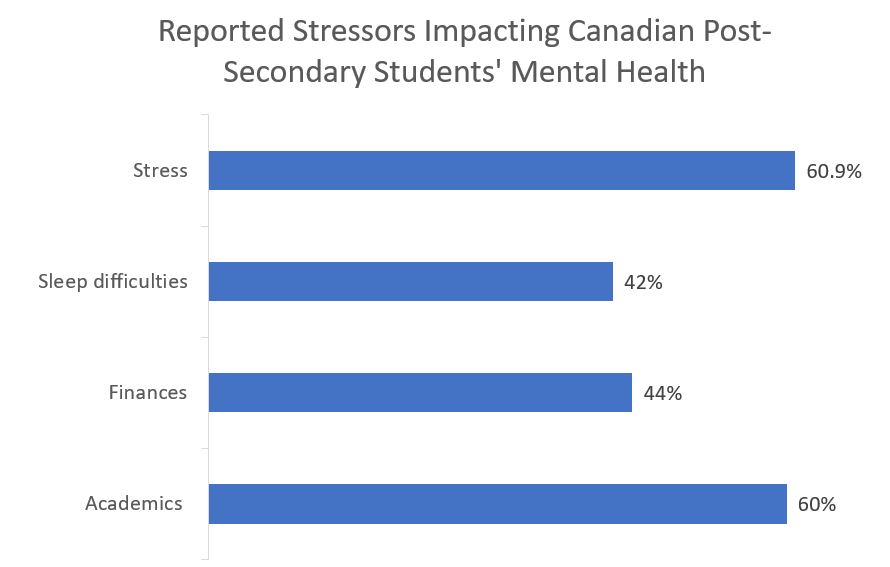

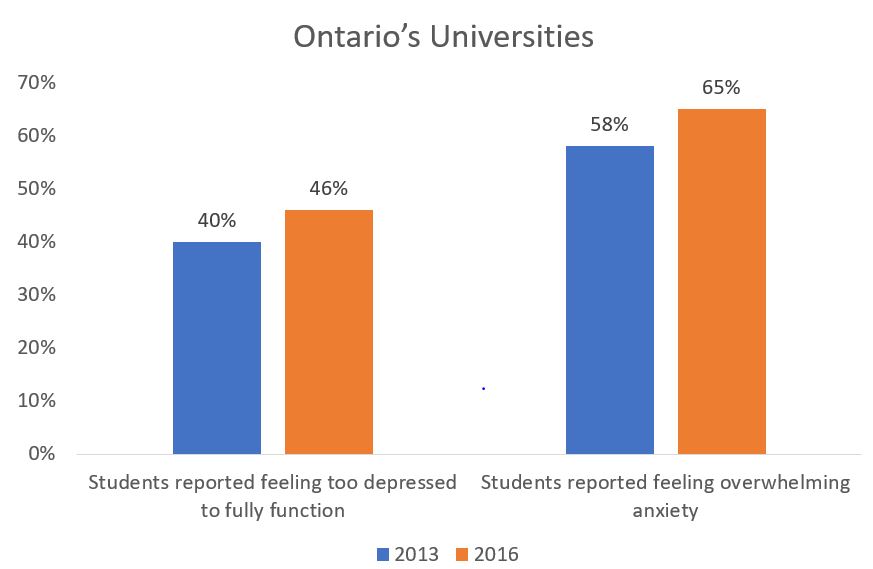

The data tells a similar story. 75 per cent of mental health illnesses appear before the age of 25, with suicide accounting for nearly 24 per cent of all deaths among 15-24-year-olds in Canada. Between 2012 and 2017, the rise in appointment requests for on-campus mental health services at the University of Toronto rose by approximately 40 per cent, while the overall student population only increased by 8 per cent.

The number of post-secondary students seeking on-campus mental health services is increasing rapidly. While this increase is likely in part due to increased awareness of available services and supports for students, the increase has put significant strain on campus support programs. The result is longer wait-times for students in need.

Inadequately addressing this rise in post-secondary student mental illness will also have a negative impact on the provincial economy more generally. In 2017, the Mental Health Commission of Canada found that 500,000 Canadians miss work each week due to mental health concerns, costing the economy billions in lost productivity. Ontario requires a healthy workforce to function and grow, however the future labour force is under threat should students continue to struggle with mental health challenges during their education.

Long Wait-Times

Even if students are aware of how and where they can access on-campus mental health services, many students are told it will take weeks – potentially months – before they can see a professional. The Canadian Alliance for Student Associations reported that wait-times to see a campus counsellor can be up to 3 months.

A survey conducted by the American College Health Association in 2019 found that 80 per cent of Canadian students had not received psychological or mental health services from their school’s counselling or health service, despite nearly 80 per cent of respondents reporting that they would be open to seeking help.

Another issue students face is a lack of awareness of what resources are available. Jack.org, a Canadian charity which trains and empowers youth to identify and dismantle barriers to mental health care services in their communities, reported that 74 per cent of students are unaware of on-campus services or how to access them.

Ontario’s post-secondary institutions do not have a mandate to deliver mental health services on-campus. These institutions are designed to deliver higher learning, not health care. However, with such a high demand among student populations, mental health threatens the quality of student health, student life, the ability to graduate, and student success more generally.

As a result, many schools have acted to provide mental health care services to their students, using additional funding from the Ministry of Colleges and Universities when available. Ontario’s colleges alone spent about $165 million more for on-campus mental health services than they received from the province, with the bulk of their contribution coming from operating budgets.

Along with in-person and e-system mental health service offerings, Ontario post-secondary institutions have developed creative ways to engage students to talk about their mental health. At the University of Waterloo, for example, a Panic, Anxiety and Stress Support kit (which includes a stress ball, ear plugs, a sleeping mask, a pack of gum and a deck of 25 flash cards with steps a student can take when they are experiencing anxiety or stress symptoms) is added to the orientation packages for first-year students.

What Government Can Do: Defining Stakeholder Roles

The first step to address the gap in the system is for the government to work with the various stakeholders to clearly define the roles they play in providing mental health care to post-secondary students. This group should include post-secondary institutions, Ontario Health Teams (OHTs), mental health care providers and agencies, and student groups. This co-ordination could even be spearheaded by the new Provincial Mental Health and Addictions Centre of Excellence once fully operational.

If possible, health care professionals within the new OHTs could be responsible for delivering on-campus care to post-secondary students within their catchment areas. However, it is unlikely that a different service provider would take on this responsibility without funding from government, as they are unlikely to fund this service because universities and colleges already are.

If universities and colleges continue to deliver these services, there are positives. Schools have the unique ability to reach entire student populations in creative and cost-efficient manners – e-mail blasts, campus engagement events and informational booths in key campus buildings, for example. Through dedicated efforts, post-secondary institutions can help increase awareness about on-campus mental health services.

Additional Resources

With additional awareness comes additional uptake of services. To meet the demand for these services, government should consider options to help universities and colleges provide a service they were never designed to provide in the first place.

First and foremost, performance metrics are necessary. Local OHTs could co-ordinate with the colleges and universities in their catchment area to create a standardized set of reporting principles and data – how many students served and wait-time reporting being two easily identifiable metrics. This reporting would ensure that the OHTs and schools are meeting demand in an efficient and comprehensive way.

Next, government should come to the table financially. One way to do so is by developing a bonus payment structure to reward positive trends in service at colleges and universities. Not only would the bonuses help universities and colleges afford the high cost of providing service, but they could be tied to continually improving targets on things like wait-times and program utilization rates.

For example, if a university or college has an average wait-time of six weeks between the time a post-secondary student first tries to access mental health care services and their first session, an incentivized approach could provide a financial bonus to the institution if they get that average wait-time below the five week mark, and even more if they get below the four week mark. Benchmarks could be continually adjusted in the future to demand even higher levels of service, ensuring the bonus payments do not simply become an additional part of the existing transfer payments to schools.

Additionally, data could be kept on metrics that are not part of the bonus payment system. For example, tracking the type and cadence of services students are accessing. Every mental health case is unique and developing an approach as such is crucial. Tracking patient outcomes using data and analytics would display quantitative proof of program efficacy. Assessing how often students are accessing services, and for how long, coupled with their success rate would be a quantitative and tangible way to assess the quality of service delivery by an institution and provide valuable insight for government policy in the future.

Lastly, the bonus payment structure creates some financial flexibility for government, as the they can ensure true value-for-money by only spending money when there are positive results. This financial flexibility is important for a provincial government that is dealing with a multi-billion-dollar deficit.

Conclusion

Solving the gap in mental health care for post-secondary students requires a structured and targeted approach to incentivize continuous improvement to resources and service delivery with a baseline focus on ensuring improved outcomes – not just simply throwing money at a problem.

The mental health crisis prevalent across post-secondary institutions will not be solved overnight. The proposed approach paves the way for government to clear the confusion between stakeholders and provide institutions with a financial incentive to better serve their student populations. A rewards system would drive continuous improvement, which in the long-term, will serve to reward institutions for successful outcomes, rather than penalize them for their shortcomings. Working in tandem to address gaps and develop comprehensive solutions is ultimately a more productive way forward.

_______________________________________________________________________

Wednesday, January 29th is Bell Let’s Talk Day. Bell will donate to mental health initiatives in Canada by contributing 5¢ for every applicable text, call, tweet, social media video view using #BellLetsTalk and use of their Facebook frame or Snapchat filter.

If you are feeling distressed you can contact any of the organizations listed below or go to a mental health walk-in clinic in your area.

Kids Help Phone:

Phone: 1-800-668-6868

Text: TALK to 686868 (English) or TEXTO to 686868 (French)

Live Chat counselling at www.kidshelpphone.ca

Post-Secondary Student Helpline:

Phone: 1-866-925-5454

Good2talk.ca