How to Avoid Ontario Teacher Strikes, Reduce the Deficit and Give Teachers a Raise All at Once

This week the Ontario Legislature returned from an extended summer break. The government has been keen to show a conciliatory and softer tone, but they have one real challenge ahead of them – impending teacher strikes. The two sides appear to be at an impasse. The government wants higher class sizes for secondary students, though they have recently weakened that stance from an average of 28 students per class to an average of 25 students per class, still up from the current average of 22.5 students per classroom. The teachers want those averages maintained at 2018-19 levels as well as keeping local caps as is and a higher pay raise, even though the government is facing a $7.4 billion deficit and is currently legislating agreements to a maximum 1% salary increase per year.

What if, financially speaking, there was a way that both sides could get what they wanted – a higher raise and a lower deficit? To show that we will explore how we got here and one idea to help resolve the stalemate for both sides.

How We Got Here:

Late in the evening on October 6 – just hours before the Canadian Union of Public Employees’ (CUPE) self-imposed strike deadline – the Province of Ontario and CUPE reached a settlement. The government barely avoided a strike from the union that represents the vast majority of school support staff like educational assistants and custodians. If a strike happened, thousands of elementary and secondary schools across the province were going to shutter their doors for the foreseeable future, causing a political nightmare.

Even though a CUPE strike was avoided, there are still 8 other central collective agreements that need to be reached, including the 4 that govern every public-school teacher in the province. Those rounds of talks have already stalled leading to Stephen Lecce, the Minister of Education, to lower the proposed increase in secondary school class size average from 28 students to 25 students.

In addition, the government has already introduced Bill 124 into the legislature, which caps all public sector bargaining contracts at a maximum 1% annual pay raise for the next three years once their deal expires. That bill should pass in the shortened fall session, meaning the teachers who have gone public with their asks for an inflationary raise of 2% or more, will have little recourse to reach a deal.

ETFO members will be concluding their strike votes by Oct 31st and OSSTF members will be voting on a strike by mid-November

How Does the Process Work?

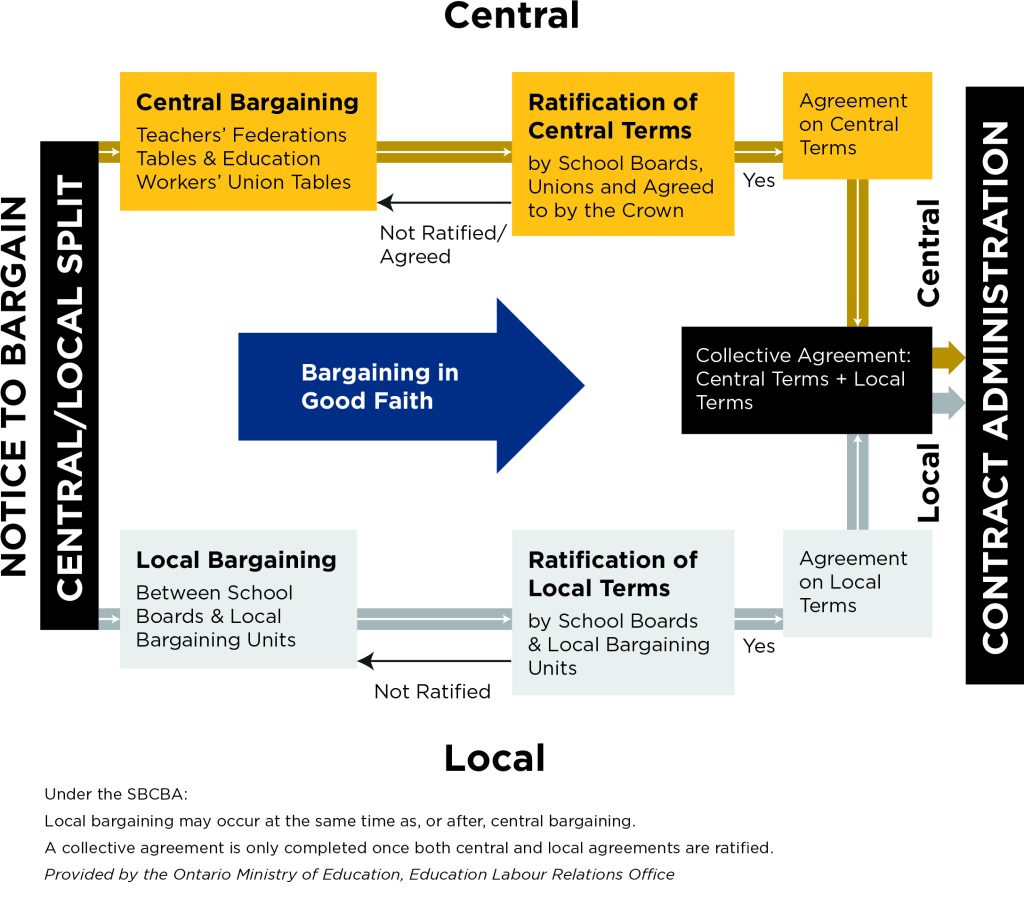

Aside from CUPE, there are 8 more central collective agreements to be reached covering all teachers and the other Educational Workers not covered by CUPE. At those 8 main negotiating tables the larger issues will be discussed, such as: pay raises, class sizes, online course requirements, and sick leave. Then, there are local negotiating tables between the 72 individual school boards in the province and their local teachers’ union where less contentious issues are usually bargained.

If the union membership votes to strike, they will be in legal position to do so within a matter of weeks. The Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario (ETFO), the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation (OSSTF) and the Ontario English Catholic Teachers’ Association (OECTA) have moved for strike votes. In fact, ETFO members will be concluding their strike votes by Oct 31st and OSSTF members will be voting on a strike by mid-November. The unions may choose only to pursue work-to-rule action before the holidays or engage in a full on strike, which is a situation the Ontario government desperately wants to avoid as it attempts to repair its image.

In addition to ETFO, OECTA and OSSTF, there is still Association Des Enseignantes Et Des Enseignants Franco-Ontariens (AEFO) to bargain with among other smaller groups. OSSTF is only public secondary school teachers, OECTA is both elementary and secondary teachers but only in the catholic system, ETFO is elementary public only, and AEFO represents all teachers in the French-language school boards.

The province will be looking to divide and conquer. By settling with one union, they can show the others that there is a path to a deal. The province has backtracked on class sizes, but they’ve so far stuck to their requirement for 4 e-learning courses in secondary school which will be taught at a ratio of 35:1. The province has also proposed slight increases to class sizes in elementary school and is committed to legislating a 1% cap on all raises for all public sector workers, including teachers, for the next three years. It is important to note that CUPE, which represents the lowest paid employees in the education sector, settled for 1%.

All told, the Financial Accountability Officer has said the move to an average 28:1 class size would eliminate 10,054 teaching positions through attrition by 2023-24. The government has been clear that it would not be firing teachers, just choosing not to replace them. It would have saved the province $2.8 billion over the next five years, including an annualized savings of $0.9 billion in the year the provincial government has stated it will reach budget balance. Instead, with the Minister’s new proposal of 25:1, those numbers will be reduced leaving the province with an even harder path to balance than it already had. Given the deadlock, and looming strikes, how can both parties reach a deal?

School Boards Collective Bargaining Act Process Map from the Ontario Public School Boards’ Association website – https://www.opsba.org/advocacy-and-action/collective-bargaining-background

The Way Out

Under the previous administration, Ontario’s Auditor General, Bonnie Lysyk, repeatedly refused to sign off on the government’s books because of a dispute related to pension accounting. That dispute revolved around two jointly sponsored pension plans between employees and the government, with the main one being the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP). Essentially, the interpretation of accounting rules changed, and the government was found to be recording the plan’s surplus on its books as an asset, despite not having the clear authority to access that money without the consent of the teachers themselves. Given the government could not demonstrate unilateral control over the funds, the Auditor did not recognize the government’s right to book that money as an asset. The Auditor did leave the door open to an agreement by suggesting the government could book the funds if they simply got a letter from the respective unions saying the government could access the funds if needed.

Ultimately, this dispute lasted for years, as the government refused to acknowledge the Auditor’s accounting and kept booking the funds anyways. The Auditor continually critiqued government, including publishing in her pre-election report that the government’s share of this accounting dispute was worth $2.6 billion in 2018-19, $3.0 billion in 2019-20, and $3.2 billion in 2020-21. This number is expected to continue to rise every year.

When Doug Ford was elected Premier, he immediately called a commission of inquiry to evaluate the state of the books. The commission recommended provisionally agreeing with the Auditor’s interpretation of the accounting dispute. The government accepted the recommendations, among others, and found itself with a $15 billion deficit to tackle. It is obvious that the government would prefer if this accounting change never happened. Having to find an extra $3 billion in savings to accommodate a paper transaction that makes no direct impact to a single Ontarian is a problem. So, here’s how to solve it:

- The asset that the government is not allowed to touch is essentially a surplus in the OTPP. Though the Ontario Public Sector Employees’ Union pension makes up a portion of the funds, the vast majority of the surplus is from the OTPP. There is only one way to make that surplus smaller, and thus reduce the over $3 billion a year figure – you must spend it.

- The government and the teachers equally contribute to the OTPP. Currently teachers contribute 10.4% of their salary if they make under $50,000 and 12% if they make over $50,000. That number is then matched by the government, bringing the total pension contribution for a teacher to more than 20% of their annual salary. Both parties also make joint decisions over significant changes within the plan, including any decision to spend the surplus. The government and the teachers must jointly agree to dispose of the funds.

- Though pensions are not a matter of bargaining at the central table, the government could propose a holiday from pension contributions outside of collective bargaining. Instead of teachers paying into their pension for a few years, they could have their pension contributions made by drawing down on the pension’s surplus. The government could even offer to contribute its half of the funding during the proposed holiday as it would already have booked this money in its fiscal plan, meaning there would be no additional costs.

- Materially speaking, teachers would receive a temporary raise worth anywhere between $3,120 and $11,082 this year depending on the length and extent of the contribution holiday. (see accompanying chart for 2019 contribution rates by salary class)

- According to the OTPP annual report (p.67), Ontario teachers’ contributions to the OTPP totaled $3.166 billion in 2018 – or roughly the exact amount of money in question under the Auditor’s accounting. Thereby one full year holiday could nearly eliminate the surplus in full or a reduced contribution rate could be used for several years to ensure the “raise” is given out over multiple years.

- Depending on the holiday negotiated, the roughly 185,000 current teachers in the province could see a raise well above the 1% the government is offering or the 2% its union is pushing for. The teachers could easily receive both the 1% raise and the pension holiday at the same time.

- For government, a proper contribution holiday would reduce their deficit substantially. They could go from $7.4 billion to approximately $4.4 billion without lifting a finger or making a single cut. It would put them substantially ahead on their path to balance and even allow them some additional financial flexibility moving forwards.

The proposal, however, does come with its fair share of risk. First, it is important to realize that the OTPP has 207,000 members who are either inactive or retired compared to 185,000 active members. Those 207,000 would not benefit from this holiday as they no longer pay dues. Therefore, traditionally, these members have preferred to spend surpluses on benefit enhancements that would help out all members.

Second, drawing down this surplus in a quick manner is not necessarily prudent pension management. Pension boards generally favour more gradual solutions like a more conservative discount rate that would slowly chip away at the surplus. OTPP already has one of the lowest discount rates in the pension business, meaning further reductions may not be welcome by the plan’s actuarial department.

Third, defined benefit pensions traditionally attempt to operate in an “over-solvent” position, meaning they have more net after-tax income than they do total debt obligations. This move would push OTPP closer to 100% solvency instead of their current solvency position (as of 2018) at 104%. If external events like recessions or unexpected dips in revenue push solvency below 100%, then contributions will rise or benefits will fall to make up the gap. Simply, if a contribution holiday dips too deeply into the surplus it could leave the plan in a riskier and more vulnerable long-term position, such as what happened in the 2000s with the OMERS pension plan.

For the reasons stated above, this idea would require a real collaborative effort from the multiple teachers’ unions engaged in talks with the province and the government itself. Though the teachers’ federations are divided up by language, level of schooling, and religion, the OTPP is not. Therefore, if one union did not agree to the deal, government would have to choose to give them a benefit anyways or risk losing other deals. In addition, there are other support staff unions that would not benefit from this deal that would still need to be bargained with.

All in all, the co-ordination needed between the relevant players would be herculean, but if the benefit is no service disruption in schools, better paid teachers, and a reduced deficit all at the same time it should be worth a shot.