StatsCan Data: Canadians Continue Moving out of Ontario and into Alberta and Atlantic Cities

Ontario has been losing residents to other provinces on a net basis for sixteen consecutive quarters.

More than 400,000 Ontarians have left the province since the first quarter of 2020. Atlantic Canada was their number one destination at the start of the pandemic until Alberta took over top spot in the third quarter of 2022.

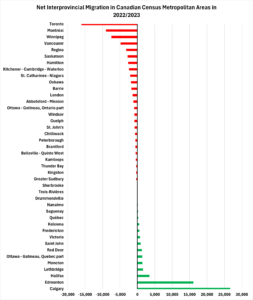

New data from Statistics Canada shows that Ontario’s interprovincial migration woes are widespread across the province. Every census metropolitan area (CMA) in Ontario lost more residents to other provinces than it attracted between July 1, 2022, and June 30, 2023 (“2022/2023”). Of the 16 CMAs in Ontario, 14 have now recorded net interprovincial migration deficits for at least three consecutive years.

Alberta and Atlantic cities gaining

At the opposite end of the spectrum, all but one CMA in Alberta and Atlantic Canada gained residents from interprovincial migration in 2022/2023. Calgary saw a record-setting net interprovincial migration surplus of 26,662. It was followed by Edmonton (+16,082) and Halifax (+3,464). Alberta and Nova Scotia might be reaping the benefits of the resident attraction campaigns each ran in recent years.

This data shows that Ontario’s major urban centers do not appear to be competitive vis-à-vis their Canadian counterparts when it comes to attracting and retaining individuals and households. This carries real economic implications as a large proportion of interprovincial migrants are between the ages of 20 and 34. These people are in prime working age.

High interprovincial migration means a highly mobile workforce. In practice, Ontario CMAs losing their appeal to Canadians may translate to local businesses struggling to recruit the best talent as they find themselves competing with employers from other provinces.

Northern Ontario seeing outflows

Also losing residents to other provinces, the two CMAs in Northern Ontario (Greater Sudbury and Thunder Bay) have been facing their own interprovincial migration challenges stemming from geography and the structure of their economies.

In 2022/2023, both Greater Sudbury and Thunder Bay saw their net interprovincial migration deficits worsen (-334 and -366 respectively).

Northern Ontario is expected to be at the center of a mining boom that will power the energy transition. This has not resulted in interprovincial migration patterns improving in Sudbury and Thunder Bay so far.

Toronto’s gravitational pull has faded

Toronto had a positive net interprovincial migration balance in the years leading up to the pandemic. However, things changed in 2020/2021 and 2021/2022 as the CMA of Toronto lost annually around 10,000 residents to other provinces on a net basis. It shattered this level in 2022/2023 by running the largest net interprovincial migration deficit ever recorded among Canadian CMAs (-16,092).

The gravitational pull of Toronto has long been attributable to its education institutions, professional opportunities and big city attractions and amenities. These pull factors are not enough to attract and retain Canadians anymore.

“Push factors” moving people out of Toronto

Three “push factors” have encouraged people to leave Toronto dating back to the first year of the pandemic. Amid public health restrictions and stay-at-home orders, many apartment and condo dwellers stuck in downtown Toronto looked to move.

The shift to remote work meant they did not have to limit themselves to the Greater Toronto Area and could instead consider other provinces as their destination.

Unlike previous waves of interprovincial migration, the current one is unique as migrants were not initially primarily driven by professional opportunities. However, this may be changing now that fewer jobs are fully remote.

The most important factor pushing people out of Toronto is housing affordability. For first-time homebuyers or families looking for a bigger house, homeownership is cheaper in other provinces.

The MLS composite benchmark price (seasonally adjusted) in the Greater Toronto Area was $1,097,300 in April 2024. This was significantly higher than cities that recorded positive net interprovincial migration like Calgary ($577,100), Edmonton ($384,000) and Halifax-Darmouth ($526,400).

Toronto also faces pressures on the rental side, which are further compounded by a large inflow of non-permanent residents who usually rent. According to the Rental Market Report from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, the average rent for a purpose-built two-bedroom apartment in Toronto was $1,940 as of October 2023. Rent for the same type of unit was $1,695 in Calgary, $1,398 in Edmonton and $1,628 in Halifax.

Toronto and Ontario CMAs are losing their appeal to Canadians as more and more families and individuals in prime working age leave for other provinces. If Ontario’s urban centres want to reestablish their competitiveness and retain residents, it undoubtedly begins with affordability.

Sebastien Labrecque is the Chief Economist and Executive Director of StrategyCorp’s Institute of Public Policy and Economy.